Virtual Lecture and Discussion, Tuesday 18 May 2021

4pm Eastern Daylight Time (NYC)

9pm British Summer Time (UK)

Organizer: Francis Fallon – fallonf@stjohns.edu

St. John’s University, New York City, USA

David Wootton is the author of The Invention of Science (2015), Power, Pleasure and Profit (2018) and other books. He has edited and translated numerous classic texts, from Machiavelli to Frankenstein, for Hackett. He was educated at Cambridge and Oxford, and has held chairs at the University of Victoria, at Brunel University, at Queen Mary University of London, and now at the University of York, in history and in political theory. He has held visiting positions at Washington University St. Louis and at Princeton.

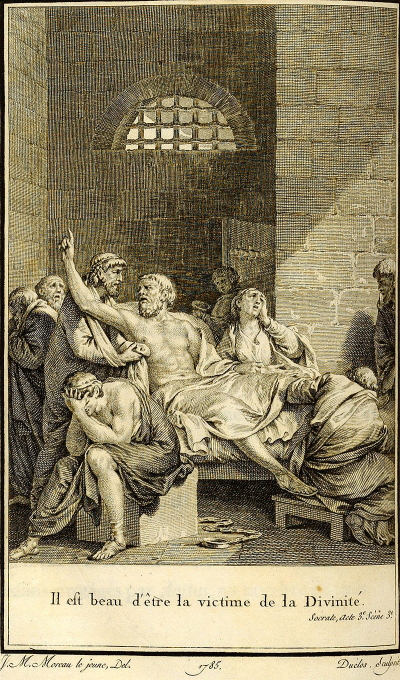

Abstract: Adam Smith thought weeping weak and unmanly, yet he acknowledged that the Romans of Cicero’s day and the Italians and the French of his own day were much given to tears. Rousseau wept frequently, but he hated the theatre, where whole audiences would weep over fictional sufferings. Voltaire, who wept at his own plays, took laughter and weeping – not reason, or an immortal soul – to be the peculiar markers of humanity. These three attitudes to tears reflect, I will argue, three different sets of moral and political values of the time. I will develop my argument by focusing on a particular real-life tragedy, the execution of Jean Calas for the supposed murder of his son. Through the case of Calas, I will explore the moral philosophy of tears, which is, I suggest, bound up with issues of justice and injustice.

Tears are inseparable from the recognition that this is not the best of all possible worlds, that, in Vergil’s words, sunt lacrimae rerum; but they imply a belief that things ought to be otherwise. Tears are thus inherently political. They are consequently an aspect — indeed a defining aspect — of Voltaire’s radicalism, and Adam Smith’s indifference to tears is a marker of his complacency about things as they are. I will, in conclusion, maintain that the moral philosophy of the French Enlightenment has significant, unrecognized virtues when compared to that of the Scottish Enlightenment.

Two texts that might be helpful in following my argument:

-Baron, Marcia. “Remorse and agent-regret.” Midwest Studies in Philosophy 13 (1988): 259-281.

-Menin, Marco. “‘Who Will Write the History of Tears?’ History of Ideas and History of Emotions from Eighteenth-Century France to the Present.” History of European Ideas 40.4 (2014): 516-532.

David’s article

David’s article  Listen to David in conversation with the journalist and Anglican priest Giles Fraser, examining the four centuries of Western thought — from Machiavelli to Madison — which led to the pursuit of success as the ultimate goal in today’s society.

Listen to David in conversation with the journalist and Anglican priest Giles Fraser, examining the four centuries of Western thought — from Machiavelli to Madison — which led to the pursuit of success as the ultimate goal in today’s society. David’s article

David’s article